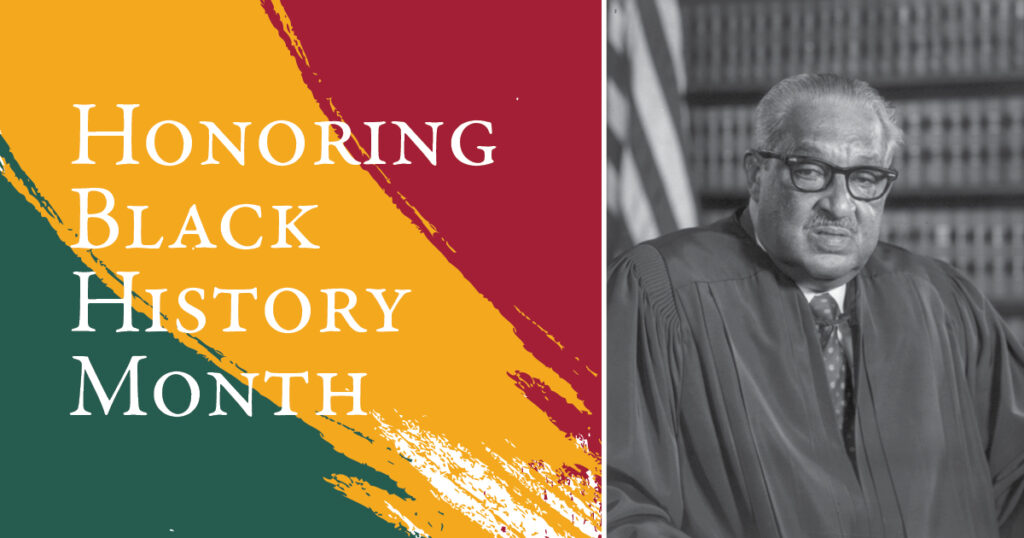

On February 8, 2024, NYLS’s Racial Justice Project hosted an event honoring the legal icon Justice Thurgood Marshall. This event was the first in a series of Black History Month events highlighting the accomplishments and contributions of Black lawyers in the legal field.

The event featured Harvard Law School (HLS) Professor Randall Kennedy, who served as a former judicial clerk of Justice Marshall and is currently the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law at HLS. Professor Kennedy was joined by Joseph Solomon Distinguished Professor of Law Rebecca Roiphe and Associate Professor of Law David Simson, and the conversation was moderated by the director of the Racial Justice Project, John Marshall Harlan II Professor of Law Penelope Andrews.

Opening remarks began by Dean of Faculty William P. LaPiana: “We are today honored to play a small part in attempting to rebut the inadequate history of racism in America today by hosting this event in honor of Justice Thurgood Marshall.”

After a series of introductions, the conversation began with a discussion of Justice Marshall’s career as an attorney in Baltimore, where he was a general practitioner of law. Then, from 1930 to 1960, he worked for the NAACP and soon became known as Mr. Civil Rights. Professor Kennedy explained that, through all of his experiences in the legal field, Justice Marshall thought he was at his best when he was acting as a trial attorney.

Both Professors Roiphe and Simson engaged Mr. Kennedy with thoughtful questions, touching upon the Supreme Court of today as compared to the Supreme Court that Marshall presided over. But the true highlights of the conversation were the personal stories that Professor Kennedy graciously shared. We were given a rare insight into the experience of being a clerk for Justice Marshall when he presided over the Supreme Court.

Professor Kennedy told us Justice Marshall was insistent on never doing or saying anything that would cast doubt on his role as a Supreme Court justice. “Justice Marshall was a rules person; law clerks would get upset with him because there were cases when a person was in prison representing themselves pro se, and they might fall afoul of a rule. Marshall was militant on this point; rules are rules, and clerks would fight him and fight him, but he was a rules person because he viewed the rules as a way for marginalized people to protect themselves. Rules could be tough, but what was tougher was arbitrariness and discrimination, and he liked rules because he thought that would be the one way people could protect themselves. There was a certain harshness about it, but it fits with him because he grew up in a very harsh environment.”

We were told that Marshall would often show up in the clerk’s office and just sit and tell stories for hours. “He knew everyone, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne, and he had stories about all of them.” Professor Kennedy went on to share stories about Marshall’s life, like the time he walked in on a private poker game with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and President Truman in order to prevent his client from being executed. We also heard a story about a near run-in with the Klu Klux Klan, and the time Justice Marshall nearly lost his life for winning a case that involved a shootout between blacks and whites in Tennessee.

A guest asked when or why Thurgood Marshall became a civil rights lawyer. Kennedy looked at us with a knowing smile. “He had a great mentor, that’s why.”

Professor Kennedy began to discuss Justice Marshall’s mentor (and the subject of the Racial Justice Project’s next Black History event) Charles Hamilton Houston, who was the reason why Marshall became a civil rights lawyer. Houston left a deep impression on Marshall and was one of the few lawyers that Marshall really respected throughout his lifetime.

Kennedy characterized Marshall as a reformer, not a revolutionary. “I think there would be a lot of people, particularly younger people, who would actually not agree with him and his stances on racial justice.” Justice Marshall was thoroughly into respectability politics, in his life as a lawyer and his life as a judge. He thought that people seeking to change things needed to be very attentive to public opinion, and he thought that if you were on the margins, you needed to bring people in, not call people out.

“His view was two steps forward, steps backward, steps to the side, etcetera, but he ultimately had a very deep faith in the United States. He deeply believed in American legal institutions and their ability to bring us to a more decent country.”

On February 20, NYLS and the Racial Justice Project will host another Black History Month event honoring legal icon Charles Hamilton Houston, Justice Marshall’s mentor and inspiration. Register to join us.