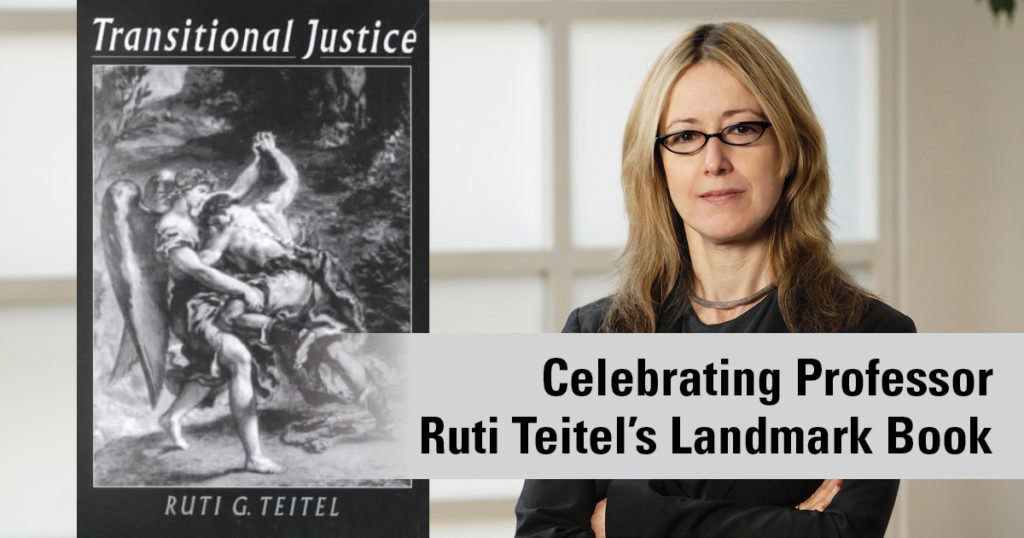

This September marked the 20th anniversary of Professor Ruti Teitel’s path-breaking book, Transitional Justice. Published in 2000, the book launched a new field—transitional justice—that applied a legal and scholarly framework to the rapid transitions to democracy many countries experienced during the late Twentieth Century.

Among the book’s critical questions were how new regimes should respond to the violence and repression of prior leaders—and the role of law and lawyers in facilitating these monumental changes.

In honor of the book’s anniversary and impact, the publisher Opinio Juris hosted a virtual book symposium, co-sponsored by Oxford University. Leading international scholars submitted commentary.

“Teitel’s Transitional Justice shed a bright light on the most fundamental phenomenon of our lifetime,” wrote Martin Böhmer, a Professor of Law at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina. “Nevertheless, the challenge that the book entailed to our scholarship, our stations, and our political commitments to look beyond that crucial moment is still to be met.”

A highlight of the symposium was a video tribute by Justice Albie Sachs, a key figure in South Africa’s transition out of apartheid.

“Ruti was the one who came out with this notion of transitional justice—and wow, there are books, there are chairs of transitional justice, there are colloquia all over the world today,” Justice Sachs said.

Q&A With Professor Teitel

What was your goal in writing the book?

We were grasping for a language with which to understand the political transitions happening in Latin America and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At that time, there was no such field to discuss it. There were political scientists and scholars who talked about regime change in the 1950s in Central Europe. Their focus was the post-World War II transitions out of fascism, and that effort was concentrated in political science, not law. But there wasn’t a field that dealt with the explosion of transition as a result of post communism and post military rule in Latin America, and post-apartheid in South Africa. It felt like a messianic moment or, in the words of the scholar Francis Fukuyama, “the end of history.”

Since Transitional Justice was published in 2000, the field has grown substantially. What is your sense of the field then versus now?

That’s very easy to answer, because there was no field before the book, and the [Opinio Juris] blog pieces reflect that. It’s been 30 years now since the political transitions I explore in the book and 20 years since the book’s publication.

I first used the term “transitional justice” in a 1991 grant application to the U.S. Institute of Peace to fund research and a volume on the topic.

I never would have predicted its lasting power. When I started using the term, people weren’t quite sure what it was. To me, the term meant that the political transitions were modifying justice. Lawyers tend to think about justice in their categories, punitive or distributive and so on.

Transitional justice has to be both forward- and backward-looking—the justice for building a new society and political community on the one hand, and accounting for the wrongs of the past, on the other. These are interrelated. Debates about whether criminal justice is about retribution or deterrence didn’t capture the interrelationship, nor did slogans, like forgiveness instead of vengeance. Equally inadequate was to simplify the idea into “peace vs. justice,” as if transitional justice was simply “real” justice compromised or diluted for the sake of moving beyond a past conflict. What was important to me was to work across those categories to show how the politics affected the theorization of law and practice at the time.

How did you structure the book with that in mind?

In researching the book, I started looking at the legal responses, the case law, the trials (some of which were essentially show trials), and the sanctions. Every chapter addresses a different area of law: for example, constitutionalism and why transitional constitutions look different than other constitutions, criminal justice and why that doesn’t look like ordinary times, and so forth.

You’ve written about the danger of viewing transitional justice as a one-size-fits-all formula. Can you explain that?

In Latin America and Eastern Europe, there were people who, though well-intentioned, would suggest applying what was done in one country to another. For example, at one conference, certain speakers were making the case that what was done post-Apartheid in South Africa with truth commissions should also be done in Hungary. I disagreed because decades earlier, Central Europe had employed truth commissions, and in that case, they were proven to be false truth, essentially false news. By contrast, South Africa had a truth and reconciliation commission that was very particular to certain religious and other traditions in that country.

My second book, Globalizing Transitional Justice, included essays that came out of discussions like this. Many were about how the interpretation of justice is subject to the political context of the society—there was a danger in universalizing the practices.

The book presents lawyers as facilitators of change rather than forces in preserving the status quo. Why is that?

I would instead say “advocates” of change. And, even beyond that, lawyers are able to see where change should occur. They can identify areas of injury and harm, and they operate with a knowledge of the past.

What role does the judiciary play during periods of transition?

For me, there’s not one judiciary. For example, in the Anglo American common law system, judges are used to the possibility of greater change and are not necessarily limited by prior cases. In Europe, the judicial system overall is more conservative, but you also have, in a number of regions now, human rights tribunals. In the Latin American system, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has done remarkable work on reparatory justice when the state has failed to protect its citizens.

In general, the domestic judiciary draw their power from the prior government and can be slow to change. So, regional human rights tribunals and criminal courts, some created by the United Nations, have played a critical role.

You were born in Argentina. How did that affect your professional pathway?

My grandparents fled Germany and Russia before World War II and settled in Argentina. When I was young, my family moved to New York City, so that my father could study at Columbia University—a yearlong fellowship that turned into a lifetime. I wrote about my father this summer, after he passed away.

In New York, I went to the United Nations school, and my father worked at the UN, though we often visited my grandparents in Argentina. Our family was very committed to issues of internationalism and human rights.

I was very excited when Raúl Alfonsín became the first democratically elected president of Argentina [in 1983]. I met him a few years later when I was attending a conference and was asked to step in and serve as his interpreter. We talked extensively, and I translated for him all day. He had run on accountability, and he’d said he would bring the military—which, in prior decades, had committed many atrocities against civilians—to justice. Under his tenure, they were largely defunded, similar to calls today to defund the police. It was a very promising and optimistic time—a moment of great hope in Latin America.

Early in his presidential term, Argentina launched the first modern truth commission, called the Nunca Más (or Never Again) Commission, to investigate human rights violations and forced disappearances by the military. That was very inspiring to me and drew me into further work on the book.

What role do private citizens (versus government regimes) play in times of national transition?

Private actors, including NGOs, often keep the drumbeat going until there’s a change in regime. We saw this in Argentina, through the heroic efforts of the “mothers of the disappeared.” Their children had been kidnapped and murdered during the period of military rule. I interviewed one of these brave women in the late 1980s. She had lost all of her children and felt that she had nothing left to lose. Figures like these also do critical work to document injustices.

I’ve been thinking lately about how journalists play this role in our country today—For example, the “1619 Project” by the New York Times has served as a sort of private truth commission. I see journalism, blogs, and social media voices moving into this space.

You’re currently working on a book about transitional justice and America.

Yes. This has been very gratifying research. I have finished a chapter on George Washington during the post-Revolutionary period and how we negotiated a reconciliation with Great Britain. This is something that is not really written about. We tend to herald the country’s separation and independence. But actually, the more significant point to my mind was that after Great Britain was humiliated by the loss of colonies, we were able to placate them to pay our debts while avoiding falling into another war. I’m also looking at the period of empire at the beginning of the 20th Century, where we have a lot of reflecting to do about the treatment of peoples in the Americas from Central America.

I will have a chapter on Lincoln and transitional justice in the post-Civil War period. I argue that Lincoln’s decision to prioritize union over equality, seen historically, appears to have presented a truly Hobbesian choice. In reflecting on the end of slavery in name, the era of segregation and Jim Crow, and now the era of mass incarceration, it is interesting to note that these shattering events have happened without any kind of truth commission or systemic reckoning. The book also explores President Obama’s belief that reckoning with the past is a mark of a mature society.

How can transitional justice shape concepts of legal education?

I have two thoughts. One is that education is critical to being a citizen, to believing in the possibility that society can change, and to being able to think about how it should change. Also, when I was writing about transitional justice, I was thinking across categories of law. The legal curriculum is largely categorized into criminal law, constitutional law, and so forth. I would make a plea for thinking in sophisticated ways about justice and jurisprudence beyond strictly formal legal categories. I’m grateful that people working in philosophy, art, politics, psychology, and other fields have been able to find something in my book. In the academy, we should be thinking about the language of justice in a broader, forward-looking way.

Professor Teitel is Co-Director of NYLS’s Center for International Law. Learn about the Center’s work.